What makes Scandinavian architecture unique? Scandinavia, using the broader cultural definition to include Finland and Iceland, punches well above its weight architecturually.

This was not always the case. Until the late nineteenth century, Scandinavia was considered an architectural lightweight, as its castles, cathedrals, and other major buildings were usually built in historical styles borrowed from abroad. Most other buildings were vernacular wooden, stone, and brick structures constructed by those without formal architectural training. Although unheralded, they offered practical solutions to problems specific to the far north, including maximizing natural light and heat during the dark, cold winter days.

Scandinavia’s architectural standing began to change in the early twentieth century as architects rejected historicism and instead blended new international styles and technological advances with elements from the vernacular traditions.

This set the stage for what became the defining traits of Scandi buildings: designs that are functional, attractive in a minimalist way, and in balance with nature. At the same time, architects played a role in the emergence of the region’s social welfare model, which required quality housing for all and public buildings for the common good.

Swedish Architecture

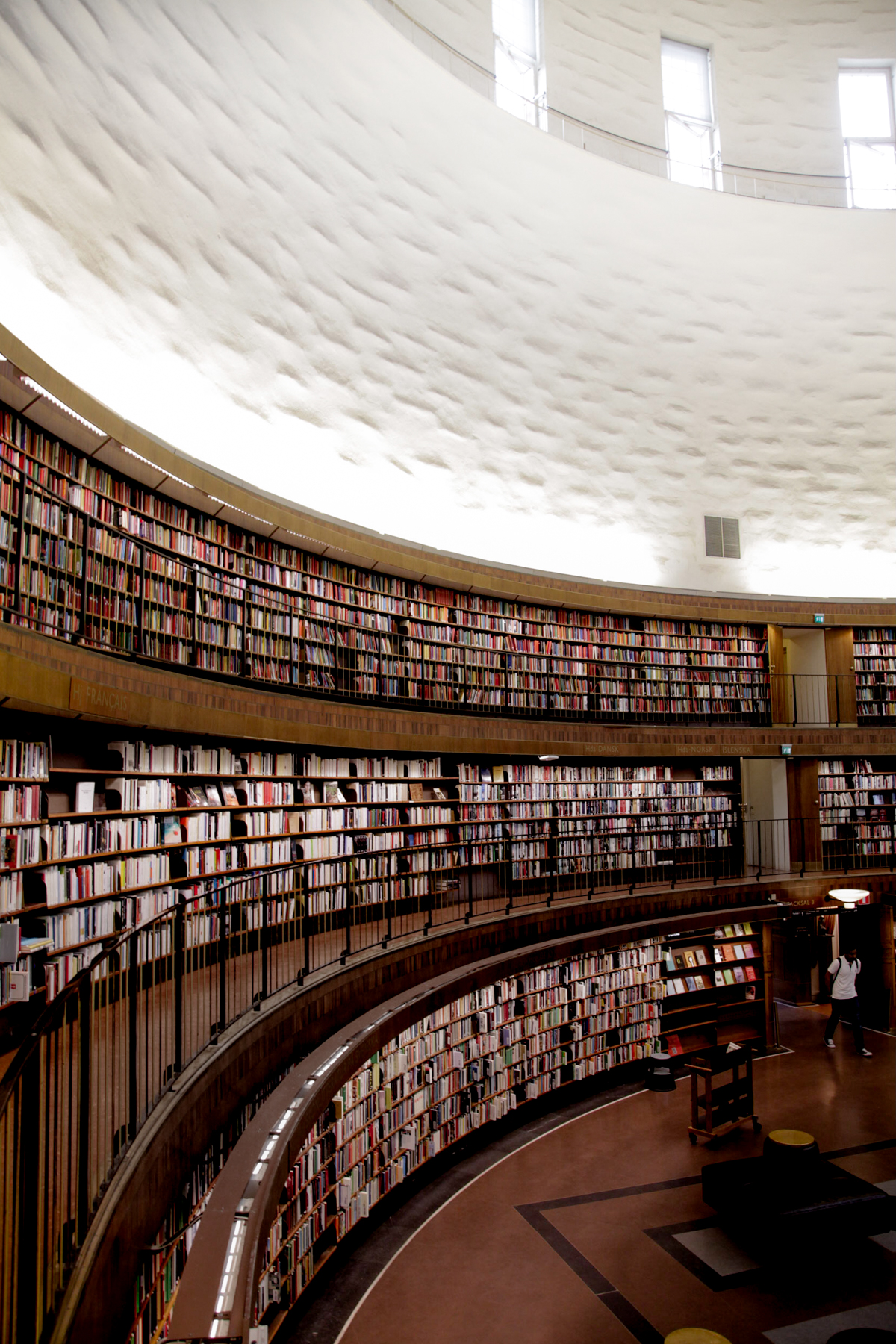

Much of the international acclaim for Scandinavian architecture in the early decades of the twentieth century can be attributed to Swedish Grace, a style mixing Neoclassicism with traditional local elements. Prominent buildings from this period include Stockholm City Hall, Stockholms stadshus, completed in 1923 by Ragnar Östberg, which London’s Observer newspaper praised as “perhaps the finest public building erected in Europe since the eighteenth century,” and the Stockholm Public Library, Stockholms stadsbibliotek, with its circular central reading room, of 1928 by Gunnar Asplund.

|

|

Stockholm Public Library, 1928 by Gunnar Asplund

|

|

Stockholm City Hall, 1923 by Ragnar Östberg

Asplund pivoted to a new direction at the Stockholm Exhibition in 1930, which he designed in an assertively Functionalist style influenced by the work of the Bauhaus and Le Corbusier. Over the next several decades, Functionalism, or Funkis for short, was Sweden’s dominant style and in the early years it yielded a number of highly regarded works combining a minimalist aesthetic with a humanistic quality often lacking outside Scandinavia. These included the Woodland Cemetery, Skogskyrkogården, of 1940 by Gunnar Asplund and Sigurd Lewerentz and Lewerentz’s St. Mark’s Church, Markuskyrkan, of 1960, both on the outskirts of Stockholm.

|

|

Woodland Cemetery, 1940 by Asplund and Sigurd Lewerentz

|

St. Mark’s Church, 1960 by Sigurd Lewerentz

Over time, design quality often became subordinated to economic and political priorities. “Swedish buildings usually work well, but they are rarely particularly innovative or fun,” architect Per Kraft noted in 2007.

More positively, there have been a number of notable projects of late, including the site-sensitive Artipelag art gallery of 2012 by Nyréns Arkitektkontor and Marge Arkitekter’s Strömkajen Ferry Terminal buildings of 2013; contemporary structures faced with tombac (a copper-zinc -alloy) that fit well with a historic waterfront area.

|

Artipelag art gallery, 2012 by Nyréns Arkitektkontor

|

|

Strömkajen Ferry Terminal, 2013 by Marge Arkitekter. Photo by Johan Fowelin

In northern Sweden, you’ll find one of the more publicly-known modern architectural feats: the Tree Hotel. This multi-structure hotel embedded into the Swedish forest features The Mirrorcube from 2010 by Tham & Videgård and The Cabin from 2010 by Cyrén & Cyrén. Both firms are well-known for their innovative and visually stunning work.

|

|

The Mirrorcube, 2010 by Tham & Videgård; The Cabin, 2010 by Cyrén & Cyrén

Finnish Architecture

“Our national identity,” the Finnish government declared in 1998, “has often found its most durable expressions through architecture.” This is attributable in large measure to Eliel Saarinen and Alvar Aalto, innovators who elevated Finnish architecture to elite status.

Blazing a path that many young rising stars of Scandinavian architecture have followed, Saarinen shot to fame by winning a number of architectural competitions while still in his twenties. Initially working with two classmates from school (receiving their first commision before graduating) and later on his own, Saarinen became the leading practitioner of a new national style fusing traditional Finnish building forms with Art Nouveau. This was a cultural triumph with political overtones at a time when Finland was part of the Russian Empire (independence came in 1917) and Swedish was the country’s primary language of government, business, and academics.

|

|

Helsinki Central Railway Station, 1919 by Eliel Saarinen

Saarinen’s masterpiece is the Helsinki Central Railway Station, built 1909 to 1919. He moved to the United States in 1923 but his absence was soon filled by Alvar Aalto, who proved to be an even bigger national hero. Aalto, influenced by Gunnar Asplund, softened the hard edges of Functionalism with organic and humanistic touches.

His pioneering works included the Paimio Sanatorium of 1933, celebrated for both maximizing light and air for tuberculosis patients and for his bentwood Paimio chair, exemplifying the connection between Scandinavian design and architecture. Much later, after designing hundreds of buildings in Finland and abroad, the capstone to his career was Finlandia Hall, a concert and conference venue in Helsinki completed in 1975.

|

Paimio Sanatorium, 1933 by Alvar Aalto

|

Finlandia Hall, 1975 by Alvar Aalto

Other notable Finnish buildings include the Temppeliaukio Rock Church of 1969 in Helsinki by brothers Timo and Tuomo Suomalainen, which placed most of the structure underground to preserve a popular hilltop park.

|

|

|

|

Temppeliaukio Rock Church, 1969 by Timo and Tuomo Suomalainen

Since then, significant projects have included the Tampere Main Library of 1986 by Reima and Raili Pietilä, with its sculptural form, and the Helsinki Central Library Oodi of 2018 by ALA Architects that uses glass and wood to create a permeable transition between its interior spaces and an adjoining public square. The Kamppi Chapel or Kampin Kappeli from 2012 designed by K2S Architects, stands as a refuge of calm and quiet within the bustling city of Helsinki.

|

Tampere Main Library, 1986 by Reima and Raili Pietilä

|

|

Kamppi Chapel, 1912 by K2S Architects

Danish Architecture

Danish architecture made a big impression locally and across Europe with the Copenhagen City Hall, Københavns Rådhus, of 1905 by Martin Nyrop, which synthesized various influences to forge a striking landmark, but it was not until 1930s that Denmark could be considered the equal of Finland and Sweden on the international scene.

|

Copenhagen City Hall, 1905 by Martin Nyrop

Several Danes embraced Functionalism and one in particular, Arne Jacobsen, emerged as an architect of the caliber of Aalto and Asplund. Jacobsen’s notable projects included an elegantly designed Functionalist beachfront community in the 1930s comprised of Bellavista Apartments, Bellevue Theater, and beach structures, including sleek lifeguard stands, on the outskirts of Copenhagen and his SAS House of 1960, his most accomplished gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) which spawned the best-selling Egg and Swan chairs.

|

|

SAS House, 1960 by Arne Jacobsen

Another important twentieth century Danish architect was Jørn Utzon, whose most famous work is the iconic Sydney Opera House of 1973, one of many beloved Scandinavian architectural exports.

|

|

Sydney Opera House, 1973 by Jørn Utzon

Currently, Danish architecture is enjoying a new golden era. At the forefront and arguably the hottest firm on the planet at the moment is Bjarke Ingels Group. Its buildings in Denmark, such as Instagram-favorite 8 House, 8-Tallet, of 2010 in Copenhagen (in the header image) and the National Maritime Museum of 2013 in Elsinore, are known for unconventional design solutions that maximize light and air and public space.

|

National Maritime Museum, 2013 by Bjarke Ingels Group

Another popular recent building is Axel Towers, completed in 2017, a commercial complex of five rounded sections of varying heights with a tombac and glass facades, by Lundgaard & Tranberg Arkitekter.

|

|

Axel Towers, 2017 by Lundgaard & Tranberg Arkitekter

Norwegian Architecture

Norway has followed the same architectural trajectory as her Nordic neighbors, but with certain distinguishing characteristics. First, Norwegian wood (the Beatles were on to something) plays an especially defining role in the nation’s architecture.

Similar to Finland, with the country receiving full independence from Sweden only in 1905, there was a patriotic desire to develop a national architectural style but this did not come as readily in Norway as it did for the Finns. No Saarinen or Aalto figure emerged to lead Norwegian architecture onto the world stage.

|

|

Oslo City Hall, 1950 by Arnstein Arneberg and Magnus Poulsson

Instead, several architects contributed to the national portfolio. These include Arnstein Arneberg and Magnus Poulsson, most famous for Oslo City Hall (designed early 1930s but not completed until 1950) with its Funkis architecture and Norwegian-themed applied art; Arne Korsmo whose highlights included the glass and concrete Villa Stenersen of 1939, later used as the prime minister’s residence; and Sverre Fehn, winner of the Pritzker Prize in 1997, whose works, such as his Glacier Museum, were noted for balancing contemporary forms with careful consideration of context.

|

|

Villa Stenersen, 1939 by Arne Korsmo

|

|

Glacier Museum, 1997 by Sverre Fehn

Following in these footsteps, the current generation has raised Norway’s architectural profile even higher, led by the internationally prominent firm Snøhetta, whose most acclaimed domestic project is the Oslo Opera House of 2008. The waterfront building with its sloped pedestrian-accessible roof and public lobby enclosed by glass and wood is credited with invigorating the capital’s cultural and design scenes.

|

|

Oslo Opera House, 2008 by Snøhetta

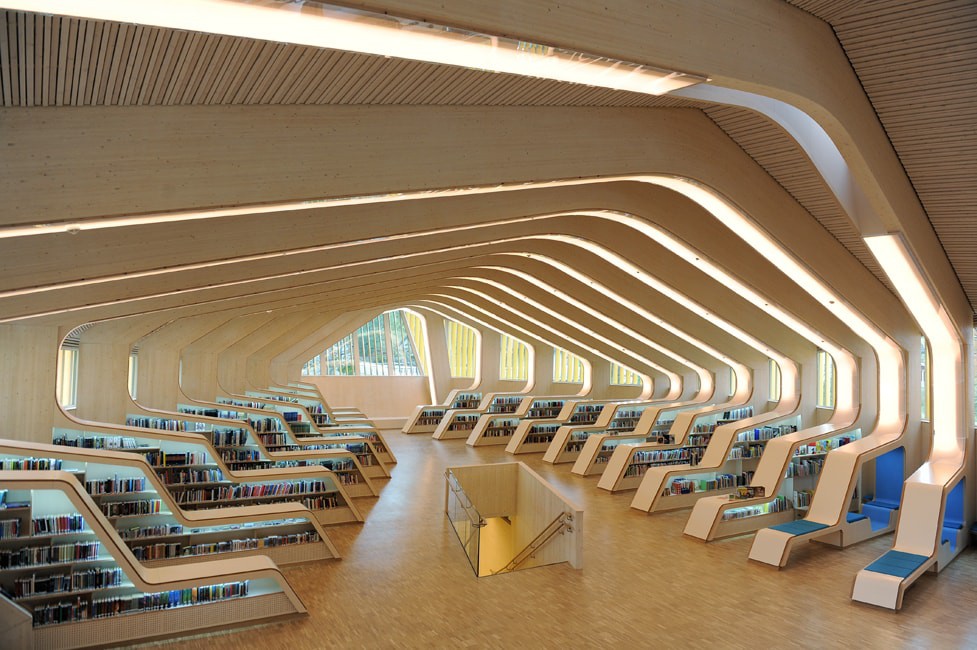

With this and other projects, such as Helen & Hard’s Vennesla Library and Cultural Centre of 2011, with its wood framed main hall, the long quest for a national style celebrated at home and recognized internationally has been realized.

|

Vennesla Library and Cultural Centre, 2011 by Helen & Hard

Icelandic Architecture

Icelandic architecture draws heavily on the island’s breathtaking natural landscapes. The country, which only became fully independent from Denmark in 1944, did not have its own native-born trained architects until the twentieth century.

The first one of note, who is credited with single-handedly defining a national style, was state architect Guðjón Samúelsson. Both his National Theater, completed 1950 though designed in the 1920s, and Hallgrímskirkja, the country’s largest church constructed in phases from the 1930s through 1980s, were built in concrete but mimic the basalt lava rock cliff columns that are a national treasure.

Modern notable buildings include Reykjavik City Hall (1992) and the Supreme Court (1996), both by married team Margrét Harðardóttir and Steve Christer of Studio Granda, which feature an assortment of facade materials including basalt.

|

Reykjavik City Hall, 1992 by Studio Granda

Of more recent vintage, the Harpa concert and conference hall of 2011, with its colored glass and metal frame exterior inspired by the crystalline texture of basalt formations, was a collaboration between Henning Larsen Architects of Copenhagen and Danish-Icelandic artist Ólafur Elíasson. Such Scandinavian architectural cross-fertilizations are common, other examples include a pedestrian bridge in Bergen, Norway by Studio Granda and a Norwegian engineering firm that opened last year.

|

|

|

|

Harpa concert and conference hall, 2011 by Henning Larsen Architects & Ólafur Elíasson

The Future of Scandinavian Architecture

Scandinavian architecture continues to respond to the challenges and opportunities of the day with creativity and innovation. Added to the longstanding priorities of functionality and balance with nature is an increasing urgency for environmental sustainability.

Snøhetta, for example, is engaged with a consortium including Swedish construction firm Skanska to produce buildings generating more energy than they consume, such as the Powerhouse Drøbak Montessori Secondary School completed in 2018 in Norway, which features solar power, geothermal wells, and energy-efficient design.

In Copenhagen, BIG’s Amager Bakke waste-to-energy plant, being completed in 2019, is reducing the city’s carbon emissions and showing that being green can also be fun by providing a rooftop ski slope.

Other problems persist, notably creating quality housing for all in an age where good design is a highly valued commodity. These issues likely will feature in the next chapters in the history of Scandinavian architecture.