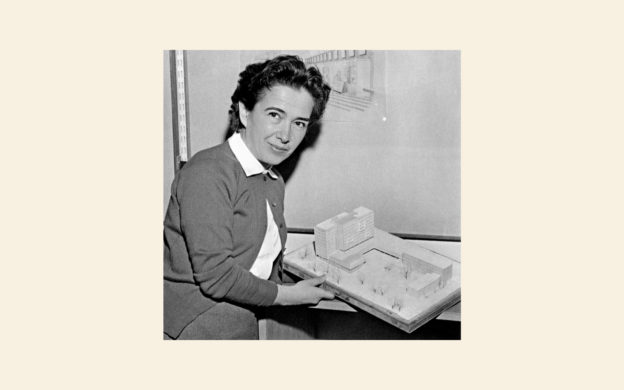

Léonie Geisendorf was one of Sweden’s most iconoclastic twentieth century architects and a trailblazer who brought an international perspective to Scandinavian architecture.

Born Leonja Kaplan in Poland in 1914, she came to Zurich in the mid 1930s for architectural studies and in 1938 graduated from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, better known by its German acronym ETH.

During that formative period, two Swiss men, both interestingly named Charles-Édouard, played important roles in her development. The first, Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (better known as Le Corbusier), mentored her as an apprentice at his Paris office in 1937-38 and his work remained an influence throughout her career. The second, Charles-Édouard Geisendorf, hailing from Geneva, was her classmate, then subsequently husband and business partner.

Although Léonie came of age in a patriarchal era, she was not a woman to be defined by the men in her life. In her own right, she established an identity based on her talent for balancing the austerity of Brutalism with warmth and humanism, powered by a strong-willed determination and a dedication to her craft.

Get to know the work of Swedish architect Léonie Geisendorf by learning about six of her most important projects:

Villa Ranängen

Villa Ranängen

In 1938, Geisendorf moved to Stockholm where she established herself both professionally and personally. She worked a series of jobs with leading Swedish architects, among them Sven Ivar Lind and Paul Hedqvist. She also married and started a family.

Geisendorf completed advanced studies at KKH, the Royal Institute of Art, where she won the Hertigliga Medaljen in 1946; the following year, in partnership with her husband and two other architects, she won an architectural competition for a municipal building. In what would become an unfortunate recurring pattern, this project was never built.

|

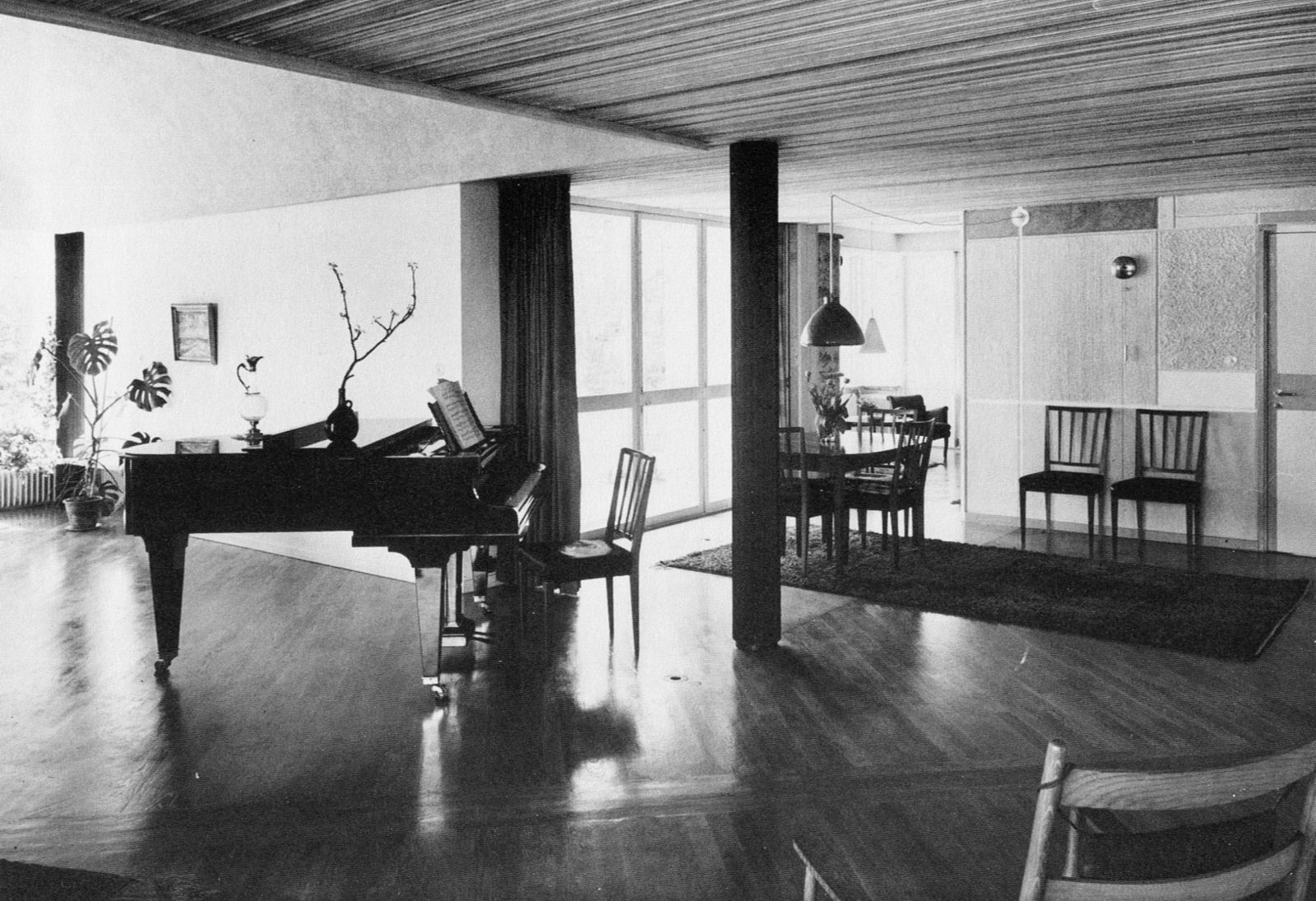

In 1950, the Geisendorfs opened their own firm, L. & C.E. Geisendorf Arkitektkontor (notice who had top billing!), and completed their first project in 1951, a suburban home. Villa Ranängen, named for a neighboring waterfront park, has a one-story, open floor plan accommodating easy access for the one of the family members who was mobility-impaired, allowing easy movement between rooms and to the rear garden. Large windows provide views to the bucolic surroundings.

The villa has a varied palette of materials, including plaster and brick walls, wood ceiling boards, parquet floors, and a dome over the living room.

|

“I so well remember the open fireplace,” Geisendorf remarked in an interview published in 2014 to commemorate her 100th birthday, “I designed it myself and I think it turned out so beautiful.” It sits on a rock-faced base, which is extended by a retaining wall in alignment with the front facade. It is modern and in harmony with its setting.

Villa Ranängen

Väringavägen 25

182 63 Djursholm

Riksrådsvägen Townhouse Area

Riksrådsvägen Townhouse Area

The Swedish government issued a report in 1953, prepared in-part by Charles-Édouard Geisendorf, promoting townhouses as an efficient form of high-quality family housing. One of the first projects built in response was the Riksrådsvägen Townhouse Area in southern Stockholm, designed by the Geisendorfs and completed in 1956.

The planned community, covering about 4.5 hectares (11 acres), includes 114 townhouses, plus one structure combining a store with a housing unit. They are grouped in several rows and arranged around a U-shaped central road, Riksrådsvägen, that is complemented by several narrow lanes branching off to provide access to the houses and common outdoor areas.

|

|

The building design is standardized, facilitating the use of prefabricated components. Instead of a single model there are three house types, with one of these types further divided into two variations.

The townhouses are each about 110 square meters and two storeys tall, though due to sloped topography several of the houses have a split stacking with three half-levels. The facades feature a medley of brick, cement, stucco, and large windows.

Many characteristics of the Geisendorfs’ work that are visible in Villa Ranängen were repeated here. The interiors are open, in this case to ease parents’ monitoring of children, and are connected to outdoor patios.

|

Another similarity is that the buildings fit in with existing landscape conditions. Retention of trees was maximized and the original city plan in which “houses were neatly and mindlessly lined up” as Léonie later described, was adjusted by “making use of the terrain so that it could give more.”

Riksrådsvägen Townhouse Area

Riksrådsvägen 35-201

128 39 Skarpnäck (Stockholm City)

Vocational School for Domestic Work and Sewing

Vocational School for Domestic Work and Sewing

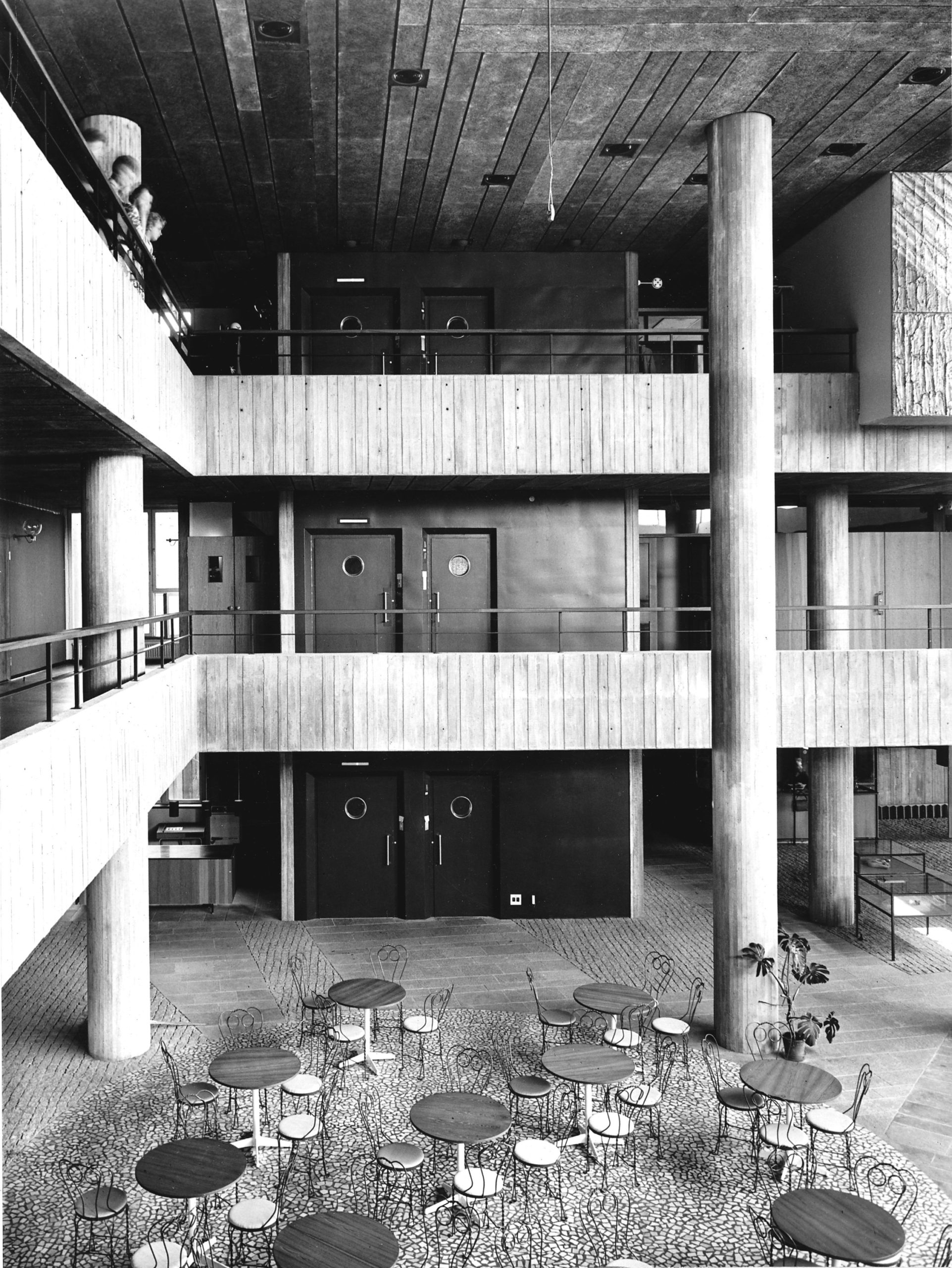

Léonie Geisendorf’s masterpiece, a vocational school in the Kungsholmen district of Stockholm, opened in 1960.

The 10-storey reinforced concrete building has expansive glass facades in a varied grid pattern interspersed with balconies. An unabashedly Brutalist building in a historic neighborhood, the school unsurprisingly attracted its share of both admirers and detractors.

Inside is where the building really shines, especially the triple-height entrance hall, which is overhung with open corridors from the floors above. With an assist from interior decorator Thea Leonhard, Geisendorf created a three-dimensional tour-de-force with plate glass windows, untreated concrete columns and walls, wood paneling and trim, sleek central staircase, and stone-paved flooring that matches the surface of the adjoining outdoor courtyard.

|

Another light-filled common area is the gym at the top level, with large windows and a clearly expressed structure of exposed concrete beams and a sloping ceiling.

Léonie took on sole responsibility for the firm’s Swedish operations in 1957, when Charles-Édouard became a professor at ETH in Zurich and opened a branch office there. That her first major project completed after this was for a school that trained mostly female students in domestic work and commercial sewing demonstrates how unconventional a figure she was.

|

|

The school was renamed St. Goran’s High School (Gymnasium in Swedish) in 1971; over the years it has adopted a broader curriculum.

The school closed in 2006 and was converted to student apartments in 2017, with the entry hall and gym preserved as common areas. The new use is ironic, given that Geisendorf’s original plan for the block called for a dormitory as well!

Vocational School for Domestic Work and Sewing

Sankt Göransgatan 95

112 45 Stockholm

Want more iconic dormitories? See the most important student housing in Copenhagen.

Fyrtalet

Fyrtalet

In 1966, Geisendorf completed a student dormitory in Stockholm’s Gärdet neighborhood. It is an area with many Swedish Functionalist apartments and institutional buildings that have rendered facades in white and pastel colors, including the Working Women’s House, a collective housing development where Geisendorf herself once lived.

In contrast, this building features seven residential storeys above a recessed two-level base, supported by large, exposed concrete columns reminiscent of Le Corbusier’s Unite d’ Habitation of 1952 in Marseilles. It is set back about 26 meters (85 feet) from the main road, Värtavägen, with parking provided both in the front courtyard and below the elevated tower.

|

Apart from red brick at the base, the exterior is predominantly clad in gray panel boards and concrete. Inset balconies at the center of the long western facade connect to student dining areas and also provide visual texture to the exterior.

This was meant to be part of a larger project consisting of four connected towers. Fyrtalet, which means a set of four, is a vestige of the original proposal.

There is currently a plan to add another student housing building, being designed by Sandellsandberg arkitekter, on the front parking lot:

|

This reflects current urban planning ideas of activating the urban streetscape with a building facing the public sidewalk, as well as providing a more appropriate use for a site located across the street from a T-bana (subway) station entrance.

Fyrtalet

Värtavägen 66

115 38 Stockholm

Villa Delin

Villa Delin

In the 1960s, a young Swedish couple who admired Le Corbusier’s famous Villa Savoye of 1931 sought to build an updated version in suburban Stockholm for their growing family. They contacted Le Corbusier, who recommended his former apprentice, giving Geisendorf an opportunity to design another home in the upscale Djursholm neighborhood.

Completed in 1970 and named for its clients, Villa Delin is Brutalist in the original meaning of the phrase, with a raw concrete (béton brut in French) exterior but is anything but brutal.

|

|

|

As in earlier projects, the building was sited to maximize the retention of existing trees and its two-storey, horizontal massing is similar to older homes in the community. It consists of rectangular volumes but rather than a simple box, portions of the ground floor are pulled back from the level above, creating sheltered terraces.

The minimalist interior features wooden floors and ceilings contrasted by whitewashed walls and black doors. The spaces are open and flowing, with sliding rather than swing doors, a double-height space in part of the living room, open staircase, and large windows on all sides for natural light.

Villa Delin Photo by Julian Cabezos / Ark Desk

With spacious common areas, a doctor’s office on the ground floor, and five bedrooms upstairs, it is unquestionably a home for an affluent family, yet represents Mid-Century Modern architecture at its unostentatious best.

Villa Delin

Strandvägen 43

182 60 Djursholm

St. Eugenia Catholic Church

St. Eugenia Catholic Church

Geisendorf had many unrealized projects and, as St. Eugenia Catholic Church exemplifies, her unbuilt work must be considered to fully appreciate her mastery.

St. Eugenia Church, built 1837, was one of hundreds of central Stockholm buildings demolished by the municipal government during the 1950s and 60s, under a major urban renewal program. The parish was offered a replacement site facing Kungsträdgården, the popular park, where it could displace yet another 19th century building.

Beginning in 1963, Geisendorf, assisted by Holger Blom, blended Modernism with respect for older buildings, by designing a new church with a concrete facade and expressing it with details and a building massing sympathetic to the area’s historic context.

The development program, which also included commercial offices and a parking garage, required another balancing act, reflected in the structure’s asymmetry.

Embracing its prominent location, a grand portico would make the sanctuary and a courtyard “perceptible and directly accessible from the street,” as Geisendorf described it in a 1965 article. That same year, several architects, including Geisendorf’s former boss Sven Ivar Lind, issued a statement that it “would enrich the city.”

Photo by Julian Cabezos / Ark Desk Nya Katolska Kyrkan

Shifts in political and economic conditions, however, caused a litany of delays. “Each time the [city’s] requirements were changed,” an American publication reported in language typical of the time, “it meant that the parish’s talented lady-architect had to draw up new plans.”

The process dragged on for 13 years. By 1976 public sentiment favored historic preservation and the church hired another architect who converted the existing building and added a rear expansion, which opened in 1982.

Dr. Charlie Gullström, the foremost Geisendorf expert, once asked the architect whether gender played a role in having so many unbuilt projects. She responded: “Possibly. I don’t know. I did say I was uncompromising! And perhaps undiplomatic sometimes. Maybe I alienated one or two now and again. So maybe that’s a female characteristic – wanting to get the job done and see it through!”

St. Eugenia Catholic Church

Kungsträdgårdsgatan 12

111 47 Stockholm

Note: Design not executed

Léonie Geisendorf’s Legacy

While best known for her designs in the 1950s to 1970s, Geisendorf lived until 2016, passing away in Paris at age 101. Besides her architecture practice, Lola, as she was called by friends, taught at the KTH School of Architecture in Stockholm and was a role model for many architects, including women such as Charlie Gullström and Rahel Belatchew.

In an email interview, Belatchew, a Swedish architect who emigrated from Ethiopia with her family as a child and studied architecture in Paris, called Geisendorf an inspiration as a rare woman architect from the Modernist era.

“Geisendorf was a passionate architect, truly committed to her work and would not accept compromises,” Belatchew told us. “Her projects demonstrate strong skills in managing different scales and a meticulous care in the details of in situ concrete.”

Above: Architect Léonie Geisendorf in her Karmann Ghia at a vintage car rally at Gärdet in Stockholm via Wikimedia Commons

Léonie means lioness, which is apropos for a woman who defied convention and created her own narrative as a pioneering architectural genius. She left an indelible mark as one of the leading architects of her adopted homeland. In recognition of this, King Carl XVI Gustaf presented the Prince Eugen Medal for outstanding artistic activity to her in 2003.

Although she lived her last years in Paris, her final resting place is a Stockholm cemetery and her legacy endures. Gullström is writing a new book about her.

Kieran Long, the director of ArkDes (Sweden’s leading architecture museum), suggested in 2017 that “Geisendorf is perhaps the most significant woman architect of the 20th century,” and has hinted in interviews that a major exhibition will be forthcoming.

Want more on Scandinavian architecture? Find out about Scandinavia’s best libraries, as well as the important works of Sigurd Lewerentz, Jørn Utzon, and Bjarke Ingels.