Enigmatic, mystical, technical; these words apply both to Swedish architect Sigurd Lewerentz (1885-1975) and his works.

He was one of Scandinavia’s leading 20th-century architects, with a long career arc that British architect Sir Peter Cook sums up as “Classicist, stripped Classicist, window and door handle manufacturer, enjoyer of cigars, encourager of guys doing naughty tubes-and-vents architecture, Romanticist, Brutalist.”

Described as aloof and stubborn in private, he did little writing or public speaking. Likewise, his buildings “have a language of their own,” suggests Swedish architect Janne Ahlin, “that is not easy to translate into spoken or written words.” Enigmatic but fascinating, which explains why Ahlin has written exhaustively about the man and his works.

He focused on details, even at the smallest scale; one story is told of him picking out individual bricks for a project and discussing with construction crews their placement. At the same time, his projects are greater than the sum of their parts – he was a genius at creating built environments that addressed the users’ functional, emotional, and spiritual needs.

We’re exploring Swedish architect Sigurd Lewerentz’s talents and accomplishments, and present six of his most important projects:

Stockholm Rowing Club Boathouse

Stockholm Rowing Club Boathouse

This small wooden building facing Stockholm’s Djurgarden island park is an asymmetrical two-storey structure used for canoe storage and rowing club meeting space. Its exterior consists of green-painted vertical planks intersected by a horizontal row of windows and capped by sloped roofs. It includes repurposed materials from spectator stands used for viewing rowing races in the 1912 Olympics, as evidenced by seat numbers visible on the ceiling planks above the ground floor.

It opened in 1913, one of Lewerentz’s first executed works. As British architect John Stewart recently wrote, it “had a freshness and clarity of expression which was more typical of his later Functionalist work than his early Classicism.”

|

|

This not only shows where Lewerentz was heading but where he had been. After completing an engineering program and apprenticing with forward-thinking German architects, in 1909 he entered the architecture program at Stockholm’s Fine Arts Academy. However, the following year he and five other students left to create the Klara Skola, a more progressive alternative school. This only lasted a year and soon after Lewerentz opened an office in partnership with another young architect named Torsten Stubelius (after 1916 Lewerentz formed his own firm).

The boathouse is still used for its original purpose and part of the upper floor can be rented for events.

Stockholm Roddförening

Lidovägen 22

115 25 Stockholm

Resurrection Chapel, Woodland Cemetery

Resurrection Chapel, Woodland Cemetery

In 1915, Lewerentz embarked on a one-time partnership with his former Klara Skola classmate Gunnar Asplund, winning a competition to design Woodland Cemetery in southern Stockholm. The two coordinated efforts but separated the work into distinct projects. The cemetery opened in 1920, though work continued for years on various elements.

|

|

|

|

Woodland Cemetery, 1940 by Asplund and Sigurd Lewerentz

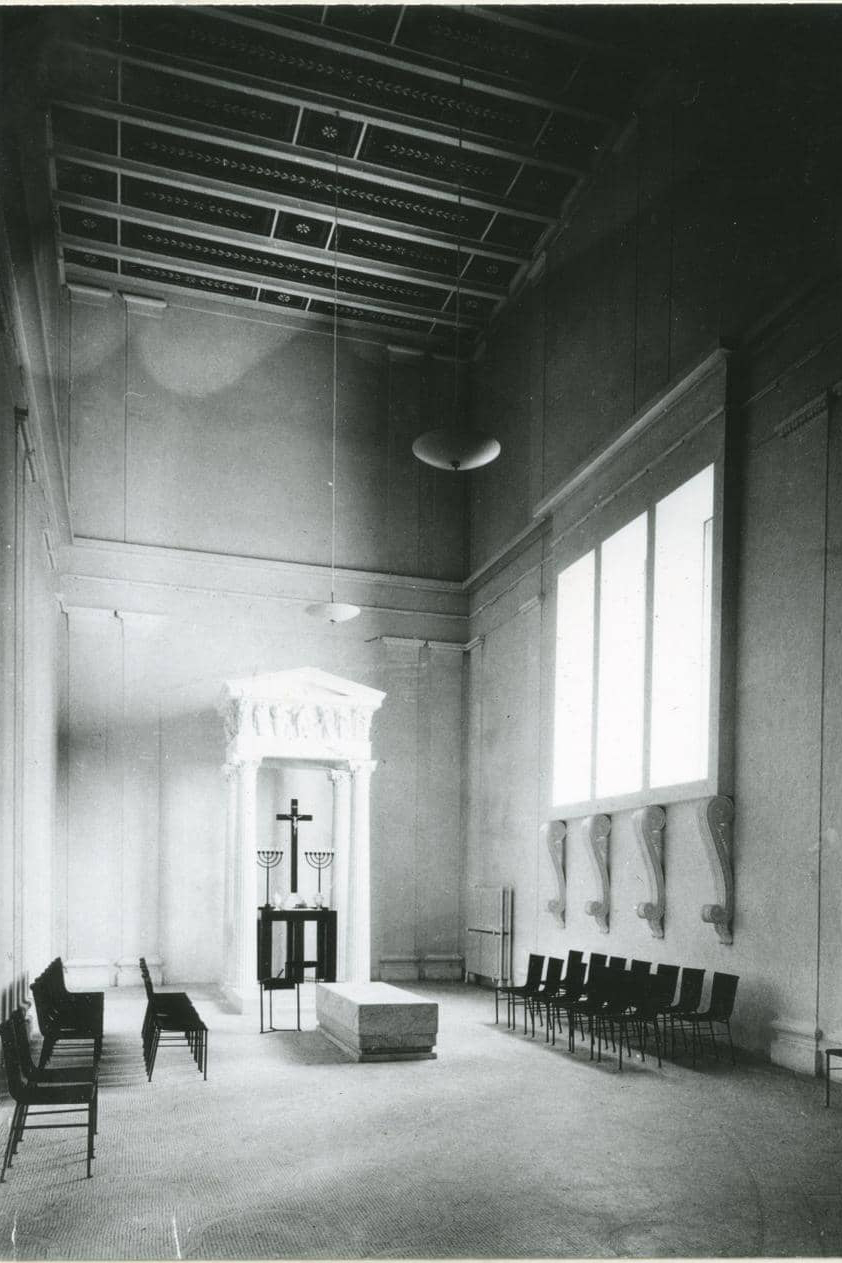

Lewerentz took on much of the site planning and landscaping but his most significant work here is the Resurrection Chapel (Uppståndelsekapellet in Swedish). Consecrated in 1925, it is a highly unconventional design and a sublime masterpiece of Nordic Classicism.

This funeral chapel is approached from the Meditation Grove, a hill to the north, by a footpath extending south through an area of mature trees interspersed with grave markers. The walkway ends at the chapel’s entry portico, a monumental entrance with Corinthian columns topped by a pediment with a sculpture depicting Christ’s resurrection.

|

|

|

|

Resurrection Chapel. Photo by Trevor Patt

The portico provides access to a sanctuary oriented east-west, requiring a 90-degree turn after one passes through the entryway. It is elegant in its simplicity, with mosaic tile floor, high ceiling, minimally decorated walls, and window on the southern wall which brings light to the front of the space. While mourners face east toward the altar and bier, above and behind them is a choir loft. The building is exited to the west via a passageway and an undecorated doorway that leads to a sunken burial garden. In turn, one ascends through this area to return to another path and the world beyond.

German architect Wilfried Wang recently praised its “invention of a cyclical procession for the mourners to affirm the continuity of life.”

Although most of the Woodland Cemetery was completed by 1940, Lewerentz continued to be involved with architectural and landscape projects there until finishing the Remembrance Garden in 1961.

Woodland Cemetery is a UNESCO World Heritage Site; public tours in English are available Sunday mornings, June to September.

Skogskyrkogården

Sockenvägen

122 33, Enskede, Stockholm

National Insurance Institute

National Insurance Institute

Another commission Leverentz won through a competition, the National Insurance Institute completed in 1932 was nicknamed the funkispalats (Functionalist palace), which captures the transitional character of this building and its times.

Designed during the late 1920s and early 1930s, the rectangular, boxy office building has a smooth, light stucco facade with symmetrical “punched” windows, a pattern reminiscent of an Italian Renaissance palazzo, albeit without the frills. The only applied decoration is a relief of the Swedish coat of arms above the main entrance.

|

|

|

|

Inside, it is more assertively Modern. At its center, there is an oval courtyard where the windows, though vertically oriented like those outside, are longer and arranged in horizontal bands offering plenty of light and air. The top floor, with an employee lunchroom, is set back from the exterior and interior walls, providing a terrace facing the courtyard.

The symmetry on the outside belies a varied layout within; a circular staircase on one end contrasts with a conventional one on the other.

Lewerentz also created furnishings and fixtures for the building through BLOKK (later renamed IDESTA), an interior design and architectural hardware firm he co-founded during this period.

The original occupant, also known in English as the Social Security Administration, remained until 2008. Subsequently, the building underwent renovations and in 2016 Marginalen Bank moved in and now hosts architectural tours, which must be booked in advance.

Riksförsäkringsanstalten

aka Kv. Grönlandet Södra 13

Adolf Fredriks kyrkogata 8

111 37 Stockholm

Malmö Opera

Malmö Opera

Opened in 1944, the Malmö Opera’s plate glass, marble, and steel-framed front facade is approached via a white marble plaza with parkland to its rear. Art is present throughout the complex, including statues by Carl Eldh and a stage curtain by Elsa Gullberg Textile Studio.

The main auditorium features both delicate design touches and technical innovations. These include a revolving stage, maple paneling, red upholstered seats, and wood partitions that can be deployed using rails embedded in the ceiling to reduce the size of the venue. In addition, the vertically adjustable fore-stage can descend to provide further audience seats or recess into an orchestra pit.

|

Lewerentz was involved with project development since the mid-1920s and won first place in two design competitions held in the mid-1930s. However, the client also liked the second-place entry by architects Erik Lallerstedt and David Helldén and asked Lewerentz to team up with them. The completed project is a hybrid of their two proposals.

Originally called the City Theater (Stadsteater in Swedish), it was (and remains) widely praised as a Functionalist triumph. “In spite of its size,” Architectural Review opined that, “the auditorium has an air of intimacy.” Educational Theatre Journal judged it “exceptionally well planned.”

|

Malmö Opera

Östra Rönneholmsvägen 20,

211 47 Malmö

St. Mark’s and St. Peter’s Churches

St. Mark’s and St. Peter’s Churches

From the early 1940s to mid-1950s, Lewerentz concentrated on IDESTA, opening a new factory in Eskilstuna, Sweden where, in the words of his contemporary Hakon Ahlberg, he lived and worked in “the beautiful flat he built for himself in the attic.” His business prospered but eventually, he reemerged architecturally with two widely praised “Brick Brutalist” buildings: St. Mark’s Church, dedicated 1960, and St. Peter’s Church, completed in 1966. The former is in Björkhagen, near Woodland Cemetery in southern Stockholm, and the latter in Klippan, a town 60 kilometers north of Malmö.

Both are constructed predominantly of rough, dark brick, used for walls, vaulted ceilings, floors, and sacramental furnishings such as pulpits, altars, and baptismal fonts. Rather than cutting bricks, Lewerentz adjusted mortar proportions to achieve desired forms. The masonry provides visual texture while other features subtly contribute to a minimalist aesthetic. For example, as Spanish architect Ingrid Campo-Ruiz has noted, “the windows in the church reflected Lewerentz’s years of research on ways to reduce the number of elements surrounding the glass pane.”

|

|

|

|

St. Mark’s Church. Photography by Rodolphe Foucher

Internal spaces are arranged based on functional and experiential considerations, such that an organizational logic is discernible. In contrast, the austere exteriors are inscrutable. British architect Sir Colin St. John Wilson wrote of St. Peter’s that “the harder you look, the more enigmatic it becomes.”

Although hailed as exemplars of Modernism, many architectural historians also see connections with earlier building traditions, including ancient Persian brickwork. Like an oracle, Lewerentz provided some hints; in brief comments on St. Mark’s he suggested that “the old architecture of Persia offers a lot to learn.” The same can be said of his works.

Markuskyrkan

Malmövägen 51,

121 53 Johanneshov, Stockholm

S:t Petri Kyrka

Vedbyvägen

264 21 Klippan

Malmö Eastern Cemetery

Malmö Eastern Cemetery

While other projects illustrate different stages and aspects of Lewerentz’s career, this project encapsulates his life’s work. He carried out site planning, landscape architecture, and building design from 1916, when he won the design competition, until the early 1970s, a testament to his longevity and versatility.

He organized the Malmö Eastern Cemetery around an existing ridge extending through the site, placing a central path along that high ground connecting the eastern and western entrances. Major buildings are placed close to the ridge with graves to the north and south. These include St. Birgitta Chapel from the 1920s in Nordic Classical style, a Functionalist crematorium from the 1930s, the twin chapels of St. Gertrud and St. Knut from the 1940s that demonstrate his mastery of building materials, and the Brutalist Flower Kiosk from the late 1960s.

|

|

|

|

Malmö Eastern Cemetery. Photography: Josep Maria Torra

He separated sections of graves by hedges, providing a more intimate scale to the large burial grounds and enclosed the entire site in trees separating it from surrounding urban areas.

Even in the early 1970s, by this point involved in the project for over 55 years, he continued on various tasks including updating plans and designing the custodian’s house.

Malmö Eastern Cemetery. Photography: Josep Maria Torra

Sigurd Lewerentz passed away in 1975, age 90. His final resting place is Malmö Eastern Cemetery.

Östra Kyrkogården

Sallerupsvägen 151

212 28 Malmö