Italian photographer Giulia Mangione was introduced to photography at an early age. On every birthday, she received a camera as a gift from her father, who was an amateur photographer.

Before she became a photographer, she studied painting but felt that the medium required technical excellence she wasn’t sure she could produce. With the photography, Guila felt in sync and discovered that she also really enjoyed meeting people as part of her work.

In 2014, Giulia traveled through Denmark during her studies at the Danish School of Media and Journalism, exploring how Danes live.

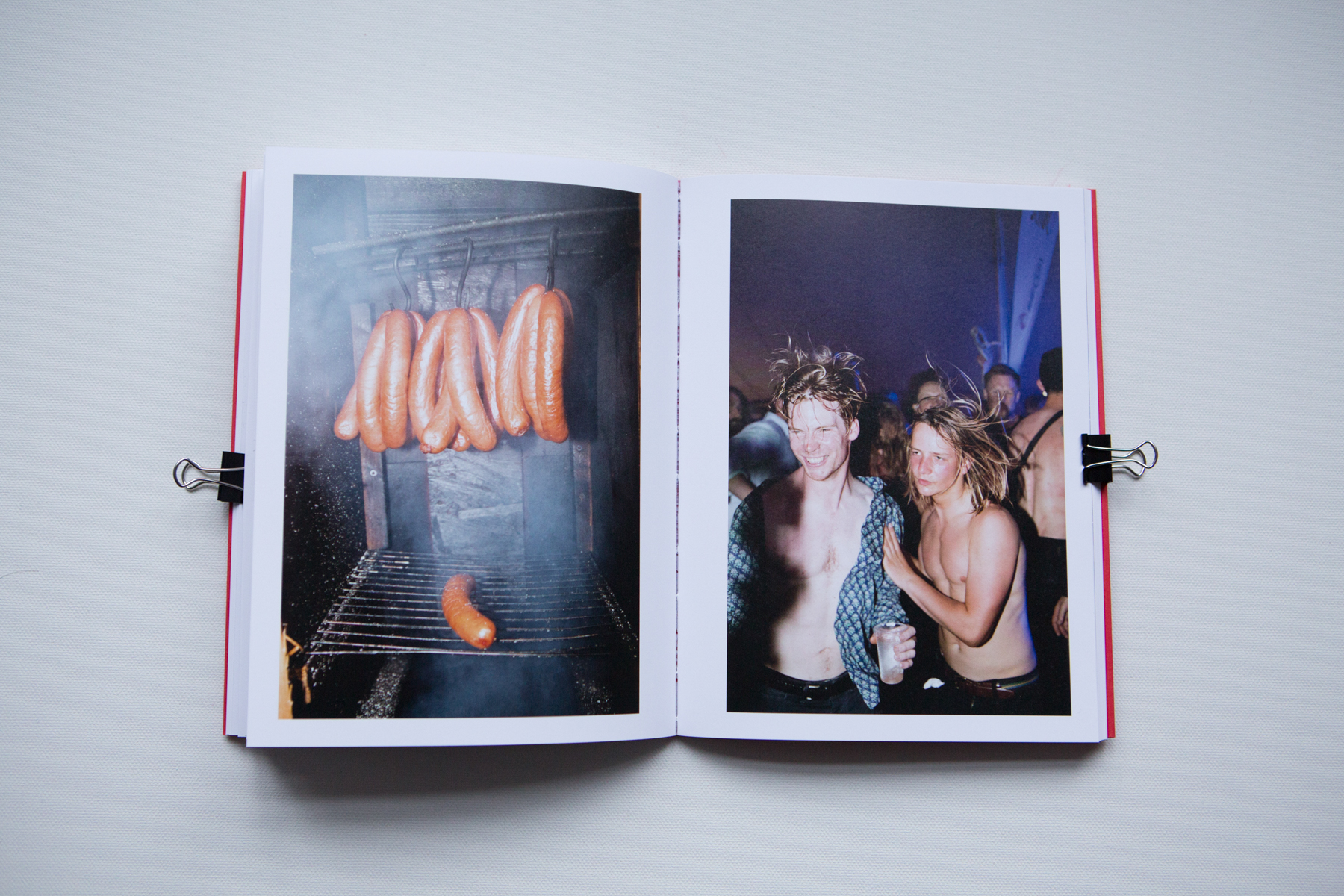

According to the World Happiness Report, Denmark was ranked as the happiest country in the world; Giulia set out to find if reality reflected this honorarium. She began depicting people around the country in joyous moments. Based on this project, I ask Giulia: what does Danish happiness look like?

|

|

“Many people asked me: are Danes really the happiest people in the world? What I found out is that Danes are often happy because their expectations are low. In Denmark, the weather is pretty bad most of the time, so when there is a little bit of sunshine in the summer they make the most of it. I think this is a very nice approach because you really use your time wisely.” Gulia explains

Having gathered plenty of interesting moments during her travels, Giulia created a book with her images: Halfway Mountain. The name was inspired by a quote from the book A Fugitive Crosses His Tracks (1933) by Norwegian/Danish author Aksel Sandemose.

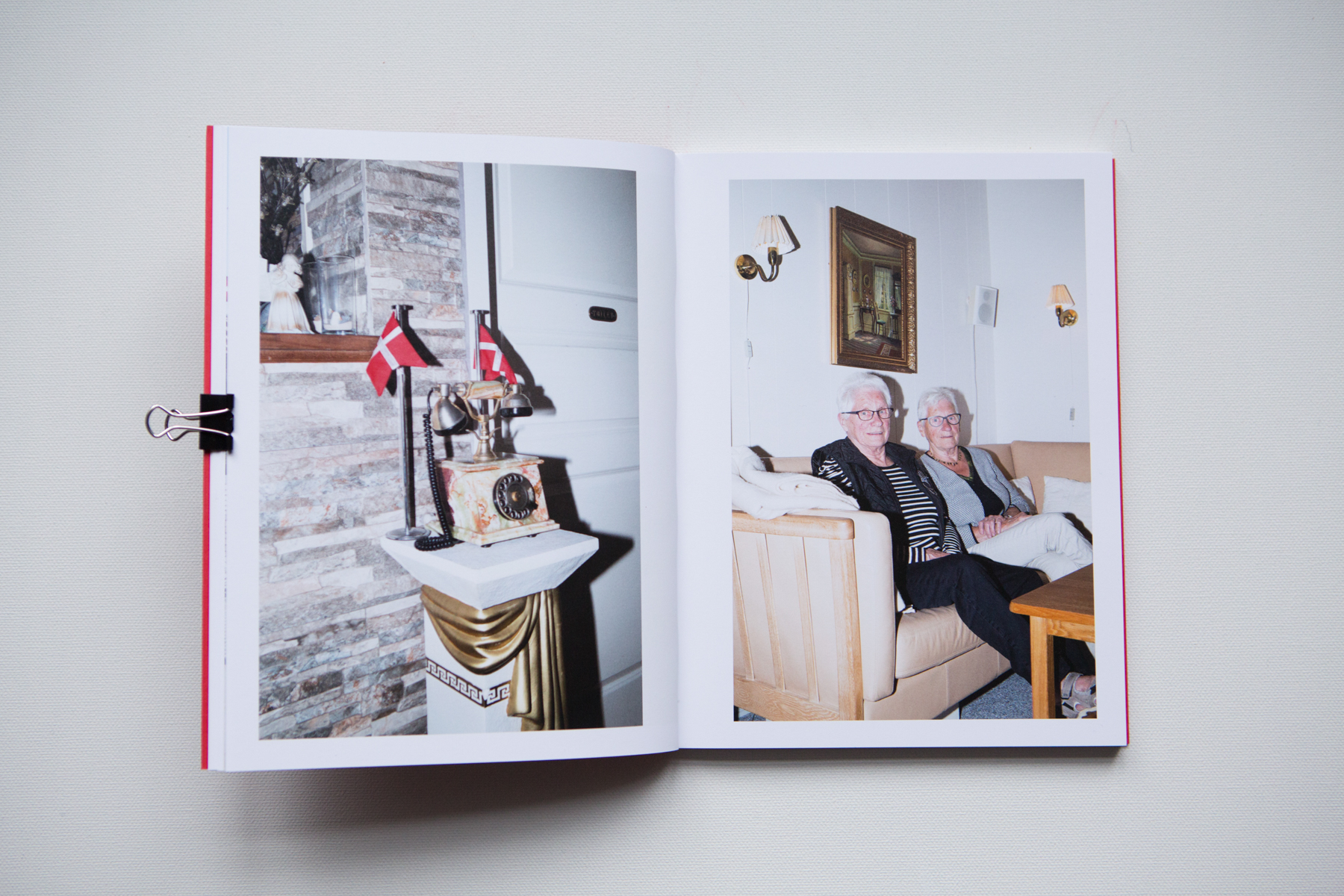

“In the epilogue of Sandemose’s book, the protagonist notes that there are many angles from which to view a mountain, and therefore multiple descriptions of the same mountain would be correct,” Giuila says. “At the beginning of my research, I was interested in finding the traditional part of Denmark. Halfway through, my research became oriented to living in ‘the happiest country in the world.’ So for me, the mountain in the quote became a metaphor for explaining happiness: something that could have many definitions but still is very difficult to put a finger on. The concept is still evanescent,” she says.

|

|

How did Giuila select the photographs that ended up in the book, I ask her. She answers: “The editing part was pretty long. It involved many people, but the most important person was Corinne Noordenbos. I took a workshop with her that helped me understand my visual vocabulary. We went through all the pictures and chose the ones that worked for the project. Originally, I wanted to do an exhibition with images printed on very cheap paper, the kind used to make street posters. But the project grew into a book.”

Gulia goes on, “after the workshop with Corinne, I went on a tour from Italy to Denmark to shoot the happiness project. I went to summer festivals and then people would invite me to parties, family celebrations, summer fairs, and so on. I am attracted to people who are (usually) a bit older and a bit extravagant. If I am in a room of 30 people, I know immediately who I want to photograph.”

|

|

I ask what she thinks about the Danish art scene and whether she felt it was inclusive. “I think it is a small circle of people, but that’s likely how it is everywhere. It’s not that easy to be part of the Danish scene, like any other scene. I’ve observed that Danish photographers prefer to work in Denmark. There are many internationally-known Danish photographers. They seem to be more interested in being famous in Denmark and Scandinavia. I don’t think I am connected to any particular location, not even Italy, because I tend to live and work in places depending on the current project. I’ve been working in Scandinavia for the past five years, but it feels early to define myself as belonging to any particular scene,” Giuila explains.

Currently, Giuila is working on a project chronicling Sweden’s fascination with America. According to her research, this is due to the fact that between 1800 and 1900, over a million Swedes immigrated to the US and still consider their relatives in Sweden to be part of their families. “There still is a strong link between people who emigrated and those who stayed,” says Giulia. We can’t wait to see the outcome of this project as it takes shape.

To purchase a signed copy of Giulia Mangione’s book Halfway Mountain, reach out to her via her website.

|

|

|

|

|