Many of us have experienced depression or times when everything seems to be falling apart. For Kari Anne Helleberg Bahri, her relief came from engaging in an activity she was passionate about. She is an example of someone who has struggled but reached the shore, with art as her rescue device.

In our interview, Kari Anne delves into the exploration of mind and soul, her curiosity for what is behind clothes, turning sorrow into art and letting go.

When did you begin working as an artist?

Having grown up with a creative mother who could do and fix anything with her hands, I started enjoying drawing, painting and making stuff from an early age. We always had ongoing projects. I’ve been told that my early age drawings were extremely rich in detail. University-age was one of the difficult periods in my life.

I don’t remember how I ended up studying art at the age of sixteen; I guess my mother decided it for me and sent me away. I think this decision saved me. After years of studying various aesthetic fields like graphic design, art, and makeup, I started an education in clothes and costume design at Oslo National Academy of the Arts. I wanted to infuse clothes into my art. After getting my Bachelor’s Degree I finally decided that this was my direction in life and started a career as an artist.

|

|

|

|

What is the idea behind using clothes in your works? What role do they play in your art?

Clothes are directly linked to people. My clothes-like objects represent personalities. I like to undress the person and show what’s behind the clothes – not the body, but the mind and thoughts.

I use clothes as a medium to tell the history of those who might have worn them. I am trying to bring the personality out of thin borders of garments that separate us from the outside world and the rest of the society. We can use these borders to express ourselves – to hide or expose.

Our clothes can tell something about our inner thoughts and history. They also reveal things about the society and how we align with it. Sometimes I use old clothes and transform them into objects that are free in form. I start with textiles like old sheets, blankets, tablecloths and transform them into clothes like objects. I call these objects ”clothes-like” as I intend to use my art as a language for telling a story and not for dressing a body.

You often multiply objects; why is that?

My work revolves around humans and the restrictions we experience as individuals. They might be the societal restrictions or the ones we inflict on each other. Since my clothes-like objects represent humans they often multiply. My focus is on people as individuals versus people as a group. I fear the group in many ways and want to see more of the personal differences.

The white shirts from the series “Caught in the web” are almost equal in size and color. For me, they represent people who are ”caught in the web” – society that wants us to be alike. The society which tells us to wear the same clothes, eat the same food, get a good job, buy a house, have children – and generally live in a certain way. If we follow those instructions, we become a homogenous group.

For me, a white shirt is a symbol of a “normal,” A4 life. It is white, clean and perfectly hides the human nature. But if you take a closer look at all the shirts, there are traces of individual stories, flaws and marks. The old textiles I use have spent time with humans.

Who or what inspires your work?

The mystery of the human mind inspires me. Chaos. The fact that mind plays with us. I get inspired by the history, imperfections, decay and flaws of the objects, buildings, nature and people. If I find a rusty old object in the street I get inspired and am willing to give it a new life or tell its fictional story. I can see beauty in this kind of things.

As for who, I love the work of Joseph Beuys, Jannis Kounellis, Doris Salcedo and the Norwegian/Bosnian artist Mesic Rus – they all show strength, rawness, materiality, pain and vulnerability.

Music is also a great inspiration for me. I often listen to Anohni. I love her soulful voice. Einsturzende Neubauten helps me get some power and David Bowie brings out different emotions in me. I need music to to enter my own world, my own head.

Is body a machine? Might it have a soul?

That’s a hard question. I guess body can be seen as a kind of machine. I like to play with the idea that we can replace our body with a machine. At least some parts of it. We already see how prosthetics transform people into superhumans. The question to ask here is how is the body connected with the mind? Can they exist without one another? Might a machine have a soul? I don’t know. I guess human can project a soul into it. We have the imagination to bring things to life.

One of your outdoor projects called “Living in a box” interprets the most important stages of life. What are those stages for you?

Through the “Living in a box” project I’ve established transitional rituals present and marked in different ways all around the world. Birth, youth, passing from childhood to adulthood, marriage, death.

Personally, the hardest stage in life was my father’s early death. It was a period of chaos, anger and the feeling of being trapped. As a teenager, I was trying to find my place, though I couldn’t find it.

Art became a way out. I could express what was going on inside me. I have used clothes as a protection most of my life. The worse I felt, the better I tried to look. In my art, I use clothes to do the opposite. So the time I decided to explore art is another important passage in my life.

There is also before and after I met my boyfriend. I now have a place where I can relax. He comforts and eases me. He is fun too. The constant restless feeling I used to have is more or less gone. I have the urge to do different things, visit new places and am not trying to escape something or yearn for someone else.

Actually, I hope for a new stage. I am waiting for the day when we find a place to live. A country, a town, a house where we will just say: let’s stay here!

|

|

|

|

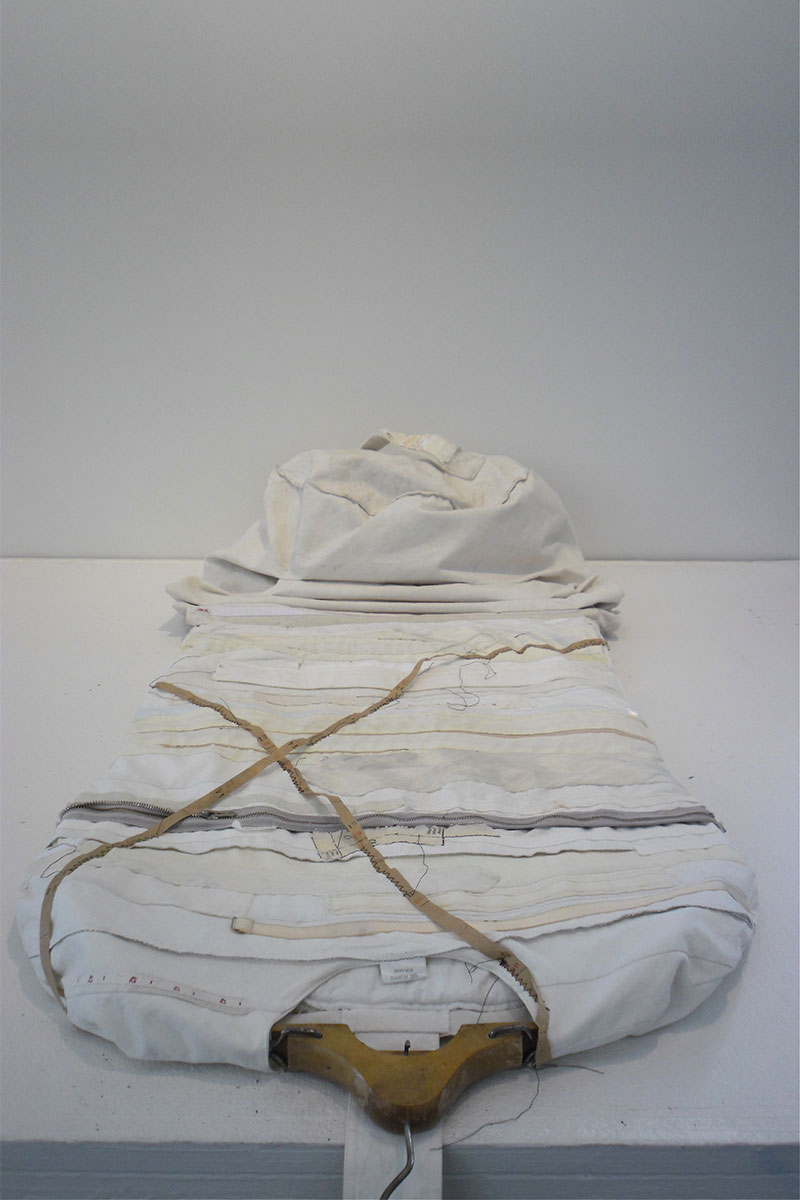

Your project Life Jacket illustrates bipolar disorder. What do you tink about depression and how can one overcome it?

Mental health is my main topic of interest. Depression is a big part of my life. It’s damn hard to do anything about it. Through the project called ”Lifejacket,” I visualized bipolar disorder by creating jackets that represented different stages of the condition. I had just met my boyfriend who is diagnosed with it. We found an affordable house for rent in an area where the mental hospital used to be. It was a beautiful place but at the same time, you could feel there was an underlying darkness. I like the combination though.

Ups and downs make people and art more interesting. But at the same time, I wish there was no depression. I know how it affects people.

The jacket is made for depression. It only fits if you are sitting down with your legs pressed against your chest. It looks a bit like a tent where you can hide. If you are depressed, it can be difficult to move. The materials used are the linings of the old jackets. I wanted the inside to be outside. This project is one of those few occasions where I made art for the body.

Limitations, restrictions, expectations and isolation. How do you define these four topics from your artistic perspective?

These are the keywords of my art. Expectations have the same meaning as limitations for me. Expectations coming from others mean that they have opinions about what somebody else should do. They may be disappointed if the person doesn’t do exactly what they had in mind. One person gets limited freedom because the other expects them to do something else.

Of course, everyone’s free to do the opposite, but for many people, the wishes of others mean a lot, especially if those wishes come from the people they like, love or look up to.

Some of my objects visualize being trapped by others. I also like to put my textile objects in wooden frames and boxes to show the restrictions we experience in our lives. The restrictions I focus on are the rules that are not written down but the common views on how to behave, how to dress, how to talk. Maybe this is more of an issue in a small country like Norway and generally in small towns and cities. There is no room for difference, I guess.

Isolation is a price we might have to pay if we don’t fit in or if we don’t follow the rules. If the adapted social rules don’t fit our personalities we might feel isolated. In any case, the fear of isolation is a basic fear in most of us and we try not to end up alone.

My installations with multiple similar objects shows people in groups who all have fear of being isolated. They may have adopted to expectations in an unhealthy way. Some of the single objects show repressive isolation. They become more formless.

|

Do you feel your art is particularly Norwegian or Scandinavian? Why or why not?

I don’t think my art is particularly Norwegian or Scandinavian. The Norwegian tendency is rather minimalistic, cold and empty. It often tends to be an installation involving different objects in a single piece.

My knowledge of a typical Scandinavian way of expression in art is minimalism. I feel quite the opposite: I am a maximalist, I like chaos. Maybe thematically, I might belong to a Nordic tradition due to the melancholy, restlessness, and depression. But in general, I think art is more global than national.

Any upcoming exhibitions?

I am at the starting point of a new exhibition. It will take place in January to February 2018. I was invited to exhibit at Akershus Kunstsenter with other three artists. We all use textiles and present identity in different ways. The keyword of the exhibition is “navigation;” How do we navigate in life and which signs do we look for to find our way.

After the exhibition at the art center, our work will turn into four individual exhibitions that will go on a tour in Akershus county – visiting sixteen different mental institutions in 2018. I think this arrangement is unique. People in difficult situation will have the opportunity to see art, meet artists and talk about their experience. This is one of the most inspiring opportunities yet in my career.

See more of Kari Anne Helleberg Bahri’s work.