Oslo-based artist Sara Skorgan Teigen constantly searches for answers in life. Her main interest lies in understanding how nature behaves and how human nature works. By mixing mediums, cutting out fragments, manipulating images, and using herself as both subject and object, Sara tries to uncover the invisible world around her.

She is attracted to things like micro/macro-cosmos and human emotions, intangible things without a physical form. What do emotions look like? Can they be captured, can they be drawn or written? How does one give life to the invisible and how can something metaphoric become existent? There is no definitive answer to these questions but the constant search for them is what makes Teigen’s work mystic and unexpected. She often finds herself in between two worlds: one that is seen, that can be photographed and documented; another which is unseen, where it is only possible to react mentally or emotionally.

She says these realities do not always correspond, but the friction is what sparks her interest. Sara’s diaries are private observations, one person’s investigation of the secrets of life. According to the artist she never sees her work as final or finished: by re-using and re-editing her photographs, she is presenting her work as a bigger process itself.

We spoke to Sara about her practice, her time in New York, and the Scandinavian art scene:

Can you tell me about yourself and how you got into photographing?

I grew up in Oslo, surrounded by musical family members [Sara’s father was the beloved Norwegian singer, musician, and comedian Jahn Teigen]. In high school, I studied theatre, but never found myself on stage. I was more attracted to the theatrical universe, the creation of the stage environment, costumes, light, etc.

After high school, I didn’t know what career to choose, and in my search found a small red camera that I got from my father when I was a kid. I soon started wondering if photography was something that one could study. Then I found Fatamorgana, The Danish School of Art Photography in Copenhagen online, and on their website, read that the students were encouraged to photograph “from the stomach.” I was amazed to read this and also to see the pictures students took. So, I decided to quit my job and went to Denmark.

The school was perfect for me, it focused on photographing what is true, rather than the technical aspect. We weren’t allowed to say anything about our pictures, which taught us what we were communicating to the world with our images alone.

|

|

|

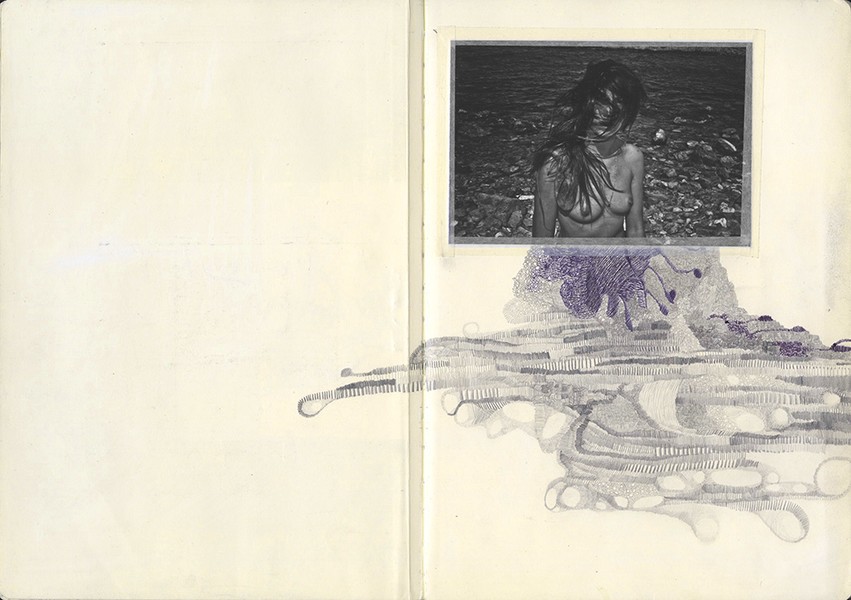

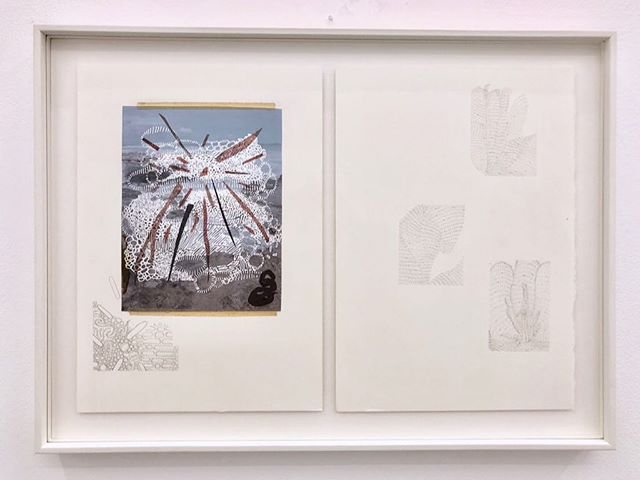

Above: Fractal State of Being (Journal 2014)

In 2011, I continued my studies in New York at the International Center of Photography (ICP). At ICP, I was introduced to alternative methods in the darkroom, color theory, philosophy, bookbinding, and contemporary thinking. After graduating, I exhibited in many places internationally, but as I worked more and more multidisciplinary, with the artist book as the primary medium (and because there is only one color darkroom in Oslo), I used classic methods less and less and worked more with manipulating the negative, scratching, cutting and making collages and photograms.

I also wanted to learn more about the old graphic methods like lithography and etching, so now I am back in school at the arts and crafts department of The National Academy of the Arts in Oslo.

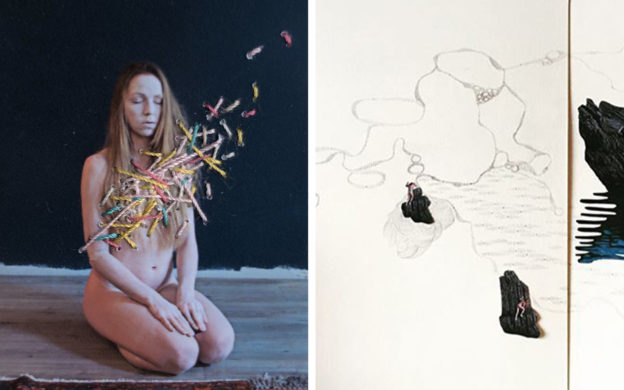

Above: Sara Skorgan Teigen Portrait from her performance ‘The Fool’

How was New York?

Arriving in New York was overwhelming. It was noisy, busy and the level of ambition was very high. Loads of new information and much bigger demands of the students than I was used to. I longed for nature and quiet. Everything went so fast, that I started drawing smaller and smaller in my sketchbook.

Photography is fast: I love how it documents the physical world, how it fits with my high tempo and stream of ideas – but drawing is a slow process.

In New York, I needed to draw more than ever, to be able to sit down and digest what was going on inside me. The sketchbook became the meeting point where the images from my final project, my experimentation in alternative mediums in the darkroom, personal notes, and drawing met. All my images were collected in the little pocket in the back of the sketchbook, and I worked simultaneously on all its pages, moving the prints back and forth in the book, trying to sort out all the new information and understand my own project.

How did working on a sketchbook transform into an artistic medium of yours?

I took a masterclass with the Swedish photographer JH Engstrôm at Atelier de Visu in France.

He saw I was drawing during class, which I always did as it helped me focus on listening. He took the sketchbook out of my hands and said it was much more interesting than my photographic project and then basically forced me to mix drawing with the photographic project I was working on.

|

|

|

Above: Fractal State of Being (Journal 2014)

Drawing had always been private for me, and I was scared to show them and mix them with photography. But I did what he said, and I am forever grateful to Engstrôm for insisting. Fractal State of Being (Journal 2014) is my first publication, and my book Interior Landscape is made in the same way – in a classical Moleskine sketchbook.

What did you discover while creating “Fractal State of Being”?

Fractal State of Being was initially made for my eyes only – it is a very honest book. It’s easy to hide what I really want to talk about when working with abstract forms but while the text is so clear… It scares me, but I decided to add text to this book.

I wrote down my dreams, cut out myself posing with swords, and included heavy symbolism. It’s embarrassing and revealing, but I needed these elements to feel that I was making the book for myself and not just for others.

|

|

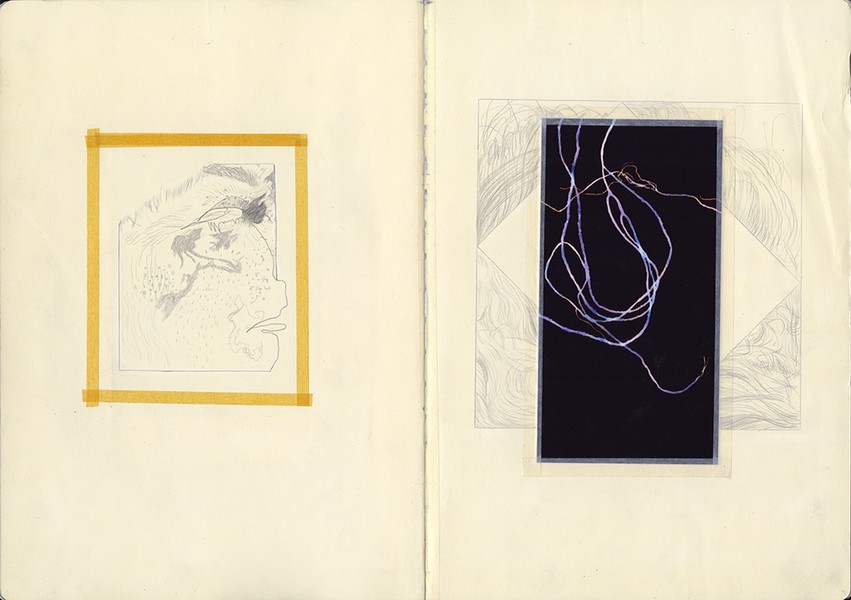

Above: Interior Landscape

Can you elaborate more on your exhibition “Interior Landscape, The Room as Sketchbook” where meditation was a big part of the project?

So many people meditate these days, as if it’s easy not to think and be completely quiet for so long. I find it difficult and I’m always disturbed by thoughts when trying, I wanted to see what [that disruption] would physically look like.

I made up an exercise where I drew lines one by one, trying my absolute best to be quiet and present in every movement. Every time I forgot about the exercise or thought about something else, I drew a little star and marked it at the bottom of the page, writing down the thought. When I finished, both the visual aspect of it and the thoughts were shocking: It was a tragicomedy! The thoughts were foolish, not connected, just pure impulses and associations. It was painful to see at first, but it was true, and the truth is what I was looking for, so I continued.

After doing this exercise many times, its point disappeared: it became too easy, so I had to challenge myself to find a new, more complicated exercise where I would be forced to concentrate by becoming a beginner again. That’s when I started sewing on my images. I was pretty surprised to find myself making sculptures of threads with letters and pictures hanging from the ceiling.

|

|

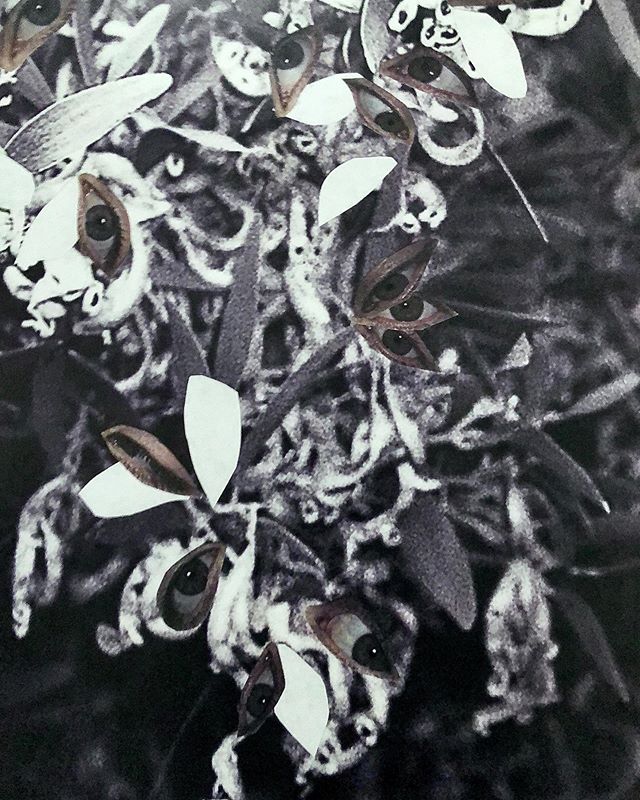

Above: Sara Skorgan Teigen “Intuition Exercise 1-3”

You are attracted to abstract matter and invisible things around. What are you trying to find through your artistic investigation?

I understood I am using the sketchbook as it has always been used: as a tool to understand and learn from nature. But instead of studying how the external world functions, I use myself as a subject and object, investigating how our inner world or experience looks and works, why we humans act the way we do. That’s why I am attracted to invisible things.

As I see it, we live in two worlds: the external world which we can see, move around in, touch and photograph, and the inner world, which is invisible, where we react to the external world. These two experiences don’t always correspond, and it is this friction I am particularly interested in.

Psychology, philosophy, hominization, religion, artforms, and art history are natural areas for me to study because they all are studies of this invisible friction, which is part of the human. My work is more than anything a necessity for myself. My visual work is just physical documentation of my personal search for understanding, meaning, and search for harmony.

The sketchbook is the most honest work I can show. And it fits me well, because the sketchbook never demands for a final conclusion or an answer, but is an investigating medium in itself.

|

|

|

Above: Interior Landscape

How do you choose between the mediums?

I am not good with words, the visual language fits me better than the spoken one, but like everyone else I need to communicate. By forcing myself to be a beginner, I learn about things and experience them. If I get too good at something, the magic is gone – I close myself from being open to learning. The human experience is what I want to learn about so, for every new project, I always go for at least one new medium.

If I want to learn about, for example, patience, I cannot photograph it because it’s too fast and I know the technique too well. I will learn much more from, for example, advanced embroidery techniques where I have to use my body in a new way and be completely present in what I am doing. It’s not the goal, but the road, which is important. That’s why the process is so interesting, the final work is just documentation of a learning process.

What do you think of the current Scandinavian art scene?

There are many good things about the Scandinavian art scene, but there’s never enough space for diversity and new blood. I miss diversity and a focus on personal expression and style – trends are dominating. The same people keep receiving the funds, which is unfortunate for the cultural scene in general.

|

Above: Interior Landscape

What are you working on currently?

Right now, I am working on publishing my second book in the sketchbook series, which will be published by Journal in 2020. Besides that, I am working on a new project, “The Fool,” which is about trauma and how to talk about what cannot be talked about. It is the first project I am working on with research in it, and I am surprised how much I love it. For this project, I am making a handmade book and using new mediums such as silent movie, text, art, and performance.